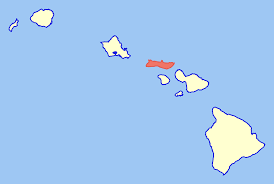

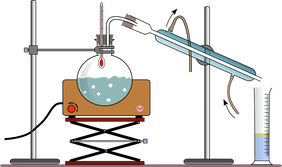

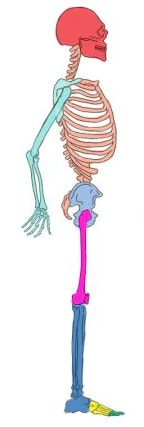

Leprosy.  It is a disease that has been around a long time. Scientists believe that leprosy originated 100,000 years ago in East Africa. From there it seems to have migrated eastward and westward (through colonization and slave trade), developing one distinct subtype in Asia and another subtype in Europe and North Africa. In western Africa, yet another distinct subtype developed. Leprosy was brought to the Americas by European colonists and western African slaves.  Dreaded and misunderstood, for centuries the disease was treated ineffectively and sometimes barbarically. In ancient Europe, Egypt, and China blood was administered--either as a beverage or as a bath. Sometimes the blood of virgins was required for ritualistic purity. The “therapeutic” use of venom from snakes, bees, scorpions, and frogs were other treatments. Some of the afflicted were scarred with irritants, including arsenic, or even endured castration!  Leprosy attacks peripheral nerves and results in acute pain. People with the disease were demonized and thought to be highly contagious. Civilizations around the world saw “lepers” as threats to the general welfare and, as a result, they were ostracized and confined to colonies to live out a lifetime of isolation. Like many other diseases, leprosy was believed to be divine punishment for worldly sins.  The disease thrived in areas with overcrowding, poor sanitation, and malnutrition. Incidence was high in Europe from about 500 – 1500 CE. Leprosy saw a decline in incidence in the 16th century, after the Middle Ages, with improved socioeconomic conditions and hygiene. Leper Colony Like its earlier migration across Africa, Europe, and the Americas, the disease was carried to the Hawaiian Islands by traders, sailors, and other workers. Hawaiians lacked immunity to the new disease, and many were infected. Without an effective treatment, the disease spread.  Concerned about their labor force, in 1865 the Hawaiian Government required all lepers to be apprehended and quarantined. Hawaiians diagnosed with leprosy were sent to Kalaupapa leper colony on Moloka’i, the fifth largest Hawaiian island. From 1866 to 1969, a total of 8,500 Hawaiian men, women, and children were exiled to Moloka’i and declared legally dead. Symptoms  Leprosy (today called Hansen’s Disease) is a disease of the nervous system. The condition attacks the body’s nerves, causing them to become inflamed under the skin. Affected areas change color, become dry or flaky, and lose all sense of feeling. The nerve damage caused by leprosy can lead to paralysis of hands and feet, reabsorption of toes and fingers, chronic ulcers, blindness, and nose disfigurement. Leprosy Etiology (Scientific Fraud #1) Physician Gerhard Hansen named Mycobacterium leprae as the causative agent of leprosy in 1873. Using a tissue sample given to him by Hansen, Albert Neisser, a microbiologist (who later discovered Neisseria gonorrhoeae, the bacterium responsible for gonorrhea) successfully stained M. leprae and announced his findings in 1880, claiming to have discovered the etiological agent of leprosy. This resulted in a dispute between Hansen and Neisser. It was not until 1897 that Hansen’s discovery was formally recognized.  These events occurred during the Golden Age of Microbiology (1850-1915), when microorganisms were shown to be the real etiological agents of infectious diseases. Hansen’s and Neisser’s works are best viewed alongside Louis Pasteur, who was renowned for his discoveries of the principles of vaccination, microbial fermentation, and pasteurization and Robert Koch, who discovered the causative agents of deadly infectious diseases including tuberculosis, cholera, and anthrax. Alice Ball (Contributor to Scientific Discovery from Under-Represented Groups) Alice Ball was born in 1892 to a family of photographers. Her grandfather, JP Ball, Sr., was one of the first African Americans to practice daguerreotype photography, a technique which involved a series of chemical processes. It was growing up in this environment that piqued Alice’s interest in chemistry.  After high school, Alice earned bachelor’s degrees in Pharmaceutical Chemistry and Pharmacy from the University of Washington. In 1915, she became the first African American—and first woman—to earn a master’s degree from the University of Hawaii. She later became institution’s first African American--and first woman--professor of chemistry.  Since her master’s thesis involved plant study, Alice’s advisor, Dr. Harry T. Hollmann, assigned her to work on chaulmoogra tree oil for the treatment of leprosy. Hollman was involved in the treatment of leprosy himself.  Chaulmoogra oil—derived from the seeds of chaulmoogra tree (Hydnocarpus wightianus) —was known to be a treatment for leprosy since the early 1300s. The treatment, however, posed problems. The oil’s main components were insoluble in water, making the oil painful to inject and difficult to absorb.  In her research, Ball was able to isolate the oil compounds and modify them to develop a substance that maintained the medicinal properties of the chaulmoogra tree yet could also be absorbed by the body when injected. The treatment of leprosy with this modified chaulmoogra oil became known as The Ball Method in 1915 Scientific Fraud #2  Shortly after her discovery, Alice Ball became ill. She had inhaled chlorine gas during a lab demonstration. (In the early 1900s, ventilation was not a required safety feature in laboratories. Alice was instructing students on how to use gas masks because chemical warfare was in use during the ongoing World War I).  According to her death certificate, Alice Ball died of tuberculosis. Irritant gases—like chlorine—can damage the lungs, making them susceptible to infections or diseases, such as tuberculosis. She was 24 when she died. Because of her illness and eventual passing, Alice never published the results of her leprosy research. Dr. Arthur Dean, the president of the university and a chemist, published her results without giving her credit. He claimed her discovery for himself, and even named the treatment “The Dean Method". In 1922, six years after Alice Ball died, Dr. Hollmann, her advisor, published a journal article that credited Ball for her work. Hollmann’s article described his enlistment of Ball on the chaulmoogra oil problem, how she did it, and its life-saving results. The article, however, did not rescue Alice Ball from obscurity.  The chemically modified chaulmoogra oil developed by Alice Ball remained the foremost treatment of leprosy until 1945. It was responsible for improving the lives of countless people. Today, there is a plaque beneath the chaulmoogra tree at the University of Hawaii bearing the name: “Alice A. Ball.” She has also been posthumously honored with a medal of distinction, a plaque, a scholarship, a film, and a park bearing her name. Leprosy is Curable: Multi-Drug Therapy Renaming leprosy Hansen’s Disease was part of an effort by health authorities to rid the condition of its social stigma and focus attention on the fact that the disease was treatable. But in 1945, oil from the chaulmoogra tree was abandoned. Dapsone (a bacteriostatic drug, which stops the microbes from reproducing) began to be used as a new treatment for Hansen’s Disease.  The duration of the dapsone treatment lasted many years, making compliance difficult. Then, in the 1950s, resistance of M. leprae to dapsone became widespread. But, in the early 1960s, rifampicin (a bactericidal drug, which kills the microbe) and clofazimine (a bacteriostatic drug that also had anti-inflammatory properties) were discovered and subsequently added to the treatment regimen. That treatment regimen was later called a multidrug therapy (MDT). The MDT lasts six to twelve months. The treatment kills the pathogen and cures the patient. With MDT it was possible to treat people with leprosy as outpatients and cease the practice of isolating them from the general population. Despite these treatments, however, as of 2021, there is still no vaccine. Two Bacteria Cause Leprosy Until the advent of molecular laboratory methods, all leprosy worldwide was assumed to have been caused by Mycobacterium leprae. In 2008, a novel Mycobacterium species, M. lepromatosis, was identified by analysis of tissue obtained from two immigrants to the US from Mexico. M. lepromatous leprosy is endemic to Mexico and the Caribbean. Comparative genomics show that M. leprae and M. lepromatosis are closely related and derived from a common ancestor Armadillos and Red Squirrels Carry Leprosy! Mycobacterium leprae is known to be transmitted to humans from nine-banded armadillos (Dasypus novemcinctus), although the mechanism is not fully understood. These armadillos are found in the mid- and south-eastern United States, as well as Mexico, Central America, and South America.  Eurasian Red Squirrels (Sciurus vulgaris) in the British Isles are the most recently discovered animal reservoir for the leprosy bacteria Mycobacterium leprae and Mycobacterium lepromatosis. DNA from leprosy causing bacteria is present in soil of regions where the disease is endemic and areas with animal reservoirs, such as armadillos and red squirrels. But Don’t Worry! The bacteria that cause leprosy cannot survive outside the body and evidence shows that 95% of all people are naturally unable to get the disease, even if they are exposed to the bacteria that causes it. People who do develop leprosy may have genes that make them susceptible to the infection once they are exposed. Worldwide, the number of leprosy cases is declining. In 2015, only 178 new cases were reported in the United States. And most cases occur in people who worked in or emigrated from developing countries. About half of the people with leprosy likely contracted it through close, long-term contact with an infected person. Casual and short-term contact does not seem to spread the disease. Once MDT leprosy treatment has begun, the disease is not contagious. Obviously, it is best to avoid contact with bodily fluids from-- and rashes on-- infected people. And, by all means, avoid contact with Fuleco, the World Cup Mascot, and Beatrix Potter’s Nutkin!

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorGertrude Katz has spent over 30 years teaching K-12 public school students all major subjects. She has taught biology and education at the college level. The majority of her career has been spent instructing biology at the secondary level. Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed